Could something prompt you to see colors that weren’t there? Or have you ever wondered why people are notorious photo of the “garment” was considered white and gold by some but blue and black by others?

After all, how can colors appear to be different from what they really are?

In some cases, the answer has to do with lighting; in others, depending on our thoughts or what our photoreceptors do, experts told Live Science.

In 2015, a photo of a dress sparked a heated debate over a simple question: What color? “The dress was unusual; we don’t really have a lot of controversy about the colors,” Bevil Conway, a neurologist and visual scientist at the National Institutes of Health in Maryland, told Live Science. “We’re not arguing about white and gold or blue and black. The disagreement is about whether those colors work in this picture or not.”

Conway and his team check the problem by asking 1,400 participants what they thought the color of the dress would be if the light was changed. They found that people’s expectations of what kind of light the dress has on affect what color they think the dress is. People who thought the dress was shot under warm or bright light thought the dress was blue and black (its actual color), while people who thought that it is cool or during the day they see white and gold.

Studies have shown that people’s perception of an object’s environment has influenced their perception of color.

Related: Why can’t we see colors well in the dark?

Memory can play an important role in how we see colors. When we look at something we are familiar with, our brain gives it the color it expects or enhances its color.

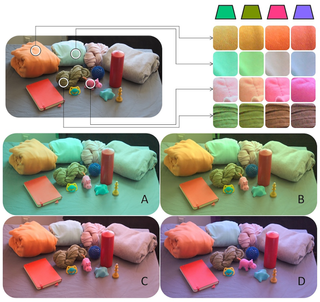

In 2024 study, the researchers asked study participants to bring colorful objects to the experiment. Next, the participants were asked to identify the color of objects under different room lights that would make the objects appear as follows:

Despite the different lighting conditions, the participants had no problems distinguishing the primary colors of the objects. This effect is called color constancy.

This effect of memory color it also explains why you tend to “see” color in the dark even when there’s no stimulating light: It’s possible that your brain constructs the color based on memory. .

On the other hand, when something is unusual, your brain can assign colors based on what you expect the object to look like. The following picture of the train was created by Akiyoshi Kitaoka, a psychologist at Ritsumeikan University, Japan. The train doesn’t have a blue pixel, even though it may appear that way to some people.

In some cases, the condition of the object or the context can make certain colors appear stronger than they really are. For example, a red object appears “redder” on a green background than on a white background. In other words, neighboring colors can change the way we see certain colors.

Tired photoreceptors

Sometimes, the cones, or colored photoreceptor cells in the retina that convert light into signals that the brain can interpret, can trick the brain into “seeing” something that isn’t there.

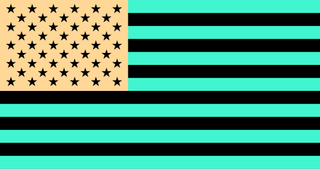

Look at this flag for 30 to 60 seconds, then focus your eyes on the white space. What do you see?

For many people, the flag is rear end, or the clear image retained after the object was removed, would appear in red and blue on a white background. This is because our photoreceptors can become fatigued.

Related: Can cats really see in the dark?

Most people have three types of color photoreceptors, or cone cells, named after the wavelengths they detect: long, medium, and short. The “long” and “middle” cone cells are the best at seeing light in the yellow wavelengths and green in the visible wavelengths. Meanwhile, the “short” cone works best to catch the “lavenderish” or violet light, Sarah Pattersonneuroscientist at the University of Washington in Seattle, told Live Science.

Our cone cells work like muscles and can get tired, Conway explained.

For example, if we look at red paper (with a long wavelength), the long cone works harder than all the other medium and short ones. If, after looking at the red paper, we turn to the white paper, the medium and short cones will compensate for the work of the long cone and create a green color that is perceived. This color scheme is called a bad feelings, or the illusion of a complementary color of an object. On the contrary, the eye can also see an image with the same color as an object that is no longer there. This color rendering is also known as a good result and usually for a very short time.

The same effect does not occur with white paper because white has all the wavelengths in it visible light. Looking at the white paper, all three types of cones are equally stimulated. Over time, the long, medium and short cones all wear out to the same extent.

There are still many things we don’t understand about how our brain perceives colors. Patterson said: “It is very difficult to ‘where’ it happens in the brain. We do not yet understand which neurons control the matching activity of the cones in the retina.

To make progress in understanding color vision, “we need more fruitful conversations between different branches of cognitive processing,” Conway said. This includes art, philosophy and science. He said that it is more than just a sight.

#missing #colors